A judge sitting in open court is largely how the public see justice being dispensed. However, the working day for a District Court Judge usually starts hours before the court doors open and ends long after the public have left.

Before a judge enters a courtroom for a hearing or trial, or to deliver a decision, a great deal has gone on behind the scenes. Judges are consulted or directly involved throughout the process underpinning District Court hearings, and much of this happens when the court is not formally sitting.

In the District Court, there is no typical working day for the nearly 200 judges because of the varied and changing nature of the tasks they perform, and the unpredictability of certain proceedings, especially trials.

The following factors give a picture of the complexity and varied nature of a judge’s working day.

These are where most people first come into contact with the District Court.

Judges sitting in criminal “list” courts deal with overnight arrests, first appearances, bail hearings, and early guilty pleas. They may hear dozens of matters in a single session. In some centres this role is also performed by Community Magistrates.

Police may object to a defendant about to appear in court being released on bail between court appearances. Applications for bail and the files relating to them and any objections, may be lengthy and need to be read before court sits, or during an adjournment and meal breaks. Judges also may have to consider at short notice applications to change bail conditions.

During adjournments and meal breaks judges usually have urgent search or arrest warrant applications from police to consider and determine.

Trials involve either a judge and jury or a judge sitting alone. Preparation for trials takes months, including holding several pre-trial hearings. In a jury trial, a judge’s final summing up can be pivotal. Judges prepare this summary of evidence for the jury when the court is not sitting. In judge-alone trials, judges must give reasons for their decisions. In 2019/20 District Court judges completed 3000 jury trial cases.

Judges hold telephone conferences in their chambers in the weeks and months leading up to a trial to deal with pre-trial matters so that when a trial starts, it runs smoothly and is not disrupted by procedural queries. The issues to be resolved may include timetabling, directions regarding procedural matters such as logistics relating to hearing evidence from vulnerable or overseas witnesses and whether certain evidence will be admissible at trial. Family Court judges also use teleconferences to assist case management and resolve some issues before hearings.

To ensure available court and judicial time is used to maximum effect, all trials have standby cases in the wings in case a matter does not proceed at the last minute, for instance when a defendant changes a plea to guilty just before or at the start of a trial. Judges have to be prepared for these standby trials.

Although most decisions are delivered in court, many are delivered later in writing because of the complexity of issues and submissions a judge may want to research and consider first. These are called reserved decisions. Judges are allotted time to write both their oral and reserved judgments. In 2019/20 District Court judges delivered 1000 reserved judgments – almost nine out of ten were delivered within three months.

Sentencing decisions are delivered in open court but take many hours to prepare, including reading files, consulting case law and considering written submissions and specialist and cultural reports. Judges are limited to the number of sentences they can each deliver in a single session to ensure quality of justice and that the court has enough time to ensure all parties and victims are heard in the time available.

Judges in the criminal court who hear opposed bail applications where violence is alleged may have a large, specially prepared file to work through before the hearing that summarises a defendant’s family violence history. The information is brought together from across the justice system to form a comprehensive pack of information. This helps a judge to determine the family violence risk of granting bail.

Most protection order applications are made in the Family Court. Judges granted 6000 protection orders in 2019/20 either on an interim or permanent basis. When time may be of the essence and in order to keep people safe, rather than wait till a formal court sitting, judges are available to consider urgent applications from anywhere in the country using the National E-Duty platform. Three to four Family Court judges a day work on E-Duty.

Most applications to the Family Court relate to disputes about care and contact arrangements for children between parents who separate. Many cases involve considering court-appointed and expert opinion and specialist reports as well as submissions from the parents or guardians and their whānau, hapū and iwi. While some hearings may take days, many related or secondary issues can be dealt with in a judge’s chambers without convening a formal hearing.

The Family Court’s second largest area of work is care and protection applications when there are concerns about a child or young person’s safety and wellbeing. The court may determine that a child needs care and protection, and can make orders, including about who a child lives with and who will be the guardians. Judges may make temporary orders if there are pressing concerns about safety. Before holding a full hearing, judges read a great deal of detailed information, specialist reports and background about a child’s development and wellbeing and family circumstances including input from whānau, hapū and iwi. Each hour of court time may represent several hours of preparation.

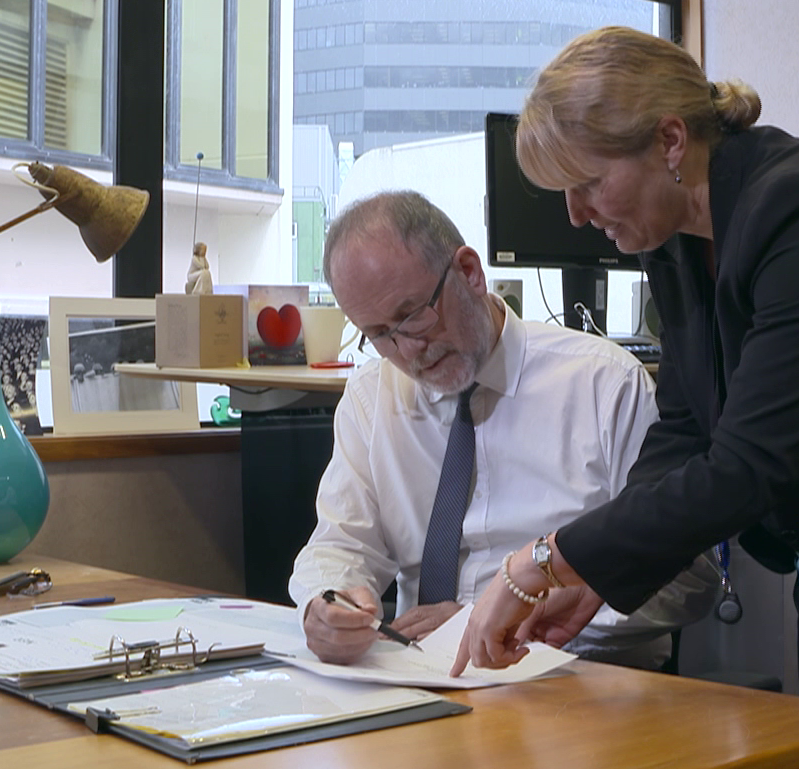

Family Court judges consider 60,000 applications a year but many matters do not require a full court hearing to be determined. Judges deal with these at their desks, “on the papers”. Family Court judges call this box work because the thick paper files may arrive in boxes on a trolley.  Reading and processing these applications take up a significant part of judge’s week.

Reading and processing these applications take up a significant part of judge’s week.

Family Court judges may be called on to determine whether a mental health patient should be receiving compulsory treatment, and this may take them into mental health institutions to hold bedside hearings. They also visit resthomes from time to time for hearings about a person’s competency to continue to manage their own affairs.

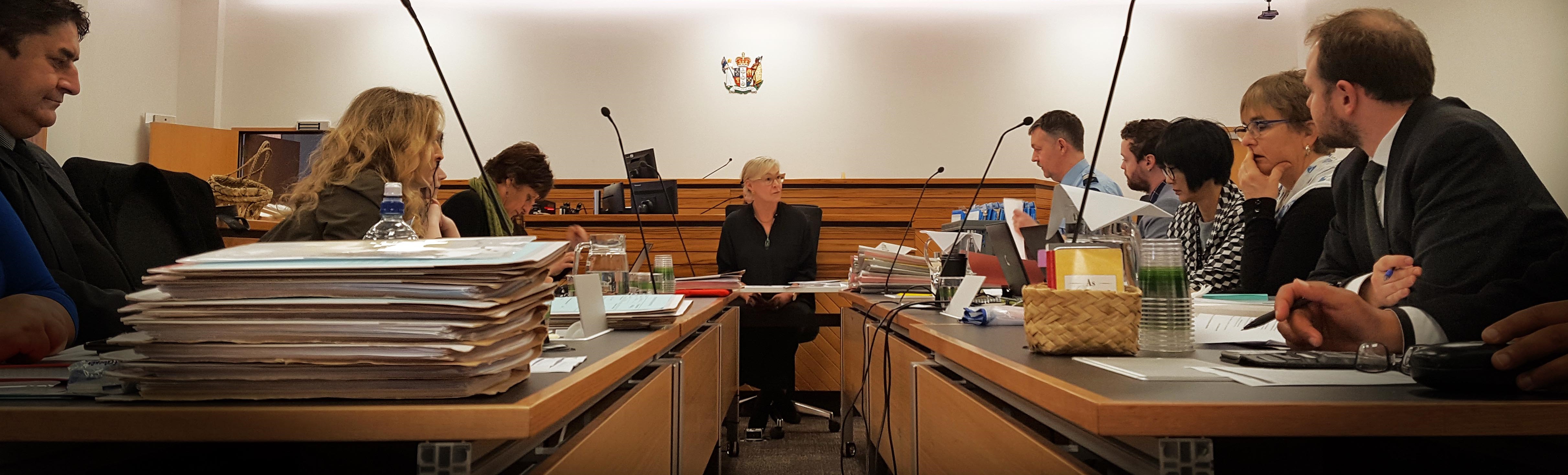

A judicial settlement conference is a type of mediation conference convened by a judge in civil and family disputes. It aims to resolve a dispute without the need for a formal court hearing, saving time, cost and emotional strain.

This work of the Youth Court is complex. Most youth in the justice system suffer at least one mental or substance disorder and one in five has a learning disability. Those appearing in the Youth Court have three times the rate of brain injury as non-offenders. For judges, addressing the underlying causes of offending requires time and patience, plus engagement with professionals who provide intervention and support. They must keep abreast of latest research on youth development, addiction, abuse and neuro-disabilities.

For judges, addressing the underlying causes of offending requires time and patience, plus engagement with professionals who provide intervention and support. They must keep abreast of latest research on youth development, addiction, abuse and neuro-disabilities.

Youth Court judges’ monitoring role may extend for many months. Before making a final decision, they call on a wide range of advice and detailed specialist reports which are often considered when court is not sitting. Some young people opt to be monitored in a process that integrates tikanga Māori, known as Ngā Kōti Rangatahi, or in a similar Pasifika Court. Judges travel to some 16 such Rangatahi and two Pasifika courts held on marae or in community venues.

Many young people are also involved in Family Court care and protection proceedings, so some Youth Court judges may perform two jurisdictional roles in one sitting, in what are called “cross-over” courts.

Increasing numbers of District Court judges have acquired expertise in specialist courts where, typically, underlying causes of offending receive intensive judicial scrutiny and case management with the active support and intervention of community agencies and iwi. These courts involve considerable preparation, case-management collaboration and information gathering with specialist agencies, outside of formal hearings. Examples include the Alcohol and Other Drug Treatment Courts in Auckland, Waitakere, the Court of New Beginnings for the homeless in Auckland, and the Special Circumstances Court in Wellington.

©Radio New Zealand.

Through these and other initiatives, many judges devote time to lead development of innovative new approaches to the administration of justice, aimed at improving access to justice and the court experience for all those who come to court. The concepts and ideas are tried, monitored and reviewed in pilot courts around the country, such as the Sexual Violence Court in Auckland and Whāngārei and the Young Adult List Court in Porirua.

The District Court sits in 58 locations, and its judges are based in the 22 biggest centres. This means judges must travel away from their home courts regularly to ensure public access to justice, and to help fill any gaps in the judicial roster. Nearly a third of court sitting time involves a judge who has travelled to another court. To ensure the travel does not impinge on court time, judges usually travel after hours on their own time.

The number of judges in the District Court fluctuates, and the legal maximum is 182 permanent judges. Of the current bench, 17 positions are currently dedicated to special roles, such as Children’s Commissioner, the Chief Coroner, the chair of the Independent Police Complaints Authority and Environment Court judges. In addition to their normal duties, four District Court judges sit on the Parole Board and one judge sits on the bench of military court martial. From time to time District Court judges also serve in courts in several Pacific countries.

The District Court usually sits from 10am but sometimes from 8.30 am for lengthy sentencing sessions. Two thirds of adult criminal court hearings finish after 4pm, leaving follow-up matters to be dealt with in what little remains of the working day. On average, the criminal court sits for four hours a day although this is figure is influenced by trials which wind up unexpectedly early, or do not go ahead because of eleventh-hour guilty pleas. The length of Family Court sessions varies and is often punctuated by adjournments as parties are encouraged to try to resolve their differences amicably outside the courtroom.

This website explains many of the things you might want to know if you are coming to the Youth Court, or just wondering how the Youth Court works.

Visit website›

Visit website›

Ministry of Justice website with information on family issues including about going to court, forms and other times when you may need help.

Visit website›

Visit website›

For information about courts and tribunals, including going to court, finding a court & collection of fines and reparation.

Visit website›

Visit website›

On this site you will find information about our Supreme Court, Court of Appeal and High Court including recent decisions, daily lists and news.

Visit website›

Visit website›