On this page you can read the 2019 proposal from Chief District Court Judge Jan-Marie Doogue and Principal Youth Court Judge John Walker for a trial of a Young Adult List in Porirua. Published 29 August 2019.

| CHIEF DISTRICT COURT JUDGE FOR NEW ZEALAND TE KAIWHAKAWĀ MATUA O TE KŌTI-Ā-ROHE Judge Jan-Marie Doogue |

PRINCIPAL YOUTH COURT JUDGE FOR NEW ZEALAND TE KAIWHAKAWĀ MATUA O TE KŌTI TAIOHI Judge John Walker |

Procedural Fairness for the Young and the Vulnerable

When a young person enters the District Court jurisdiction they bring with them all the disabilities they may have had since childhood, together with those that they may have gathered along the way. These disabilities do not have an expiry date.

Our courts have come to recognise the mitigatory effect of youth in a sentencing context, often referring to the underdeveloped brain and the inability to assess consequences when justifying this factor as one which reduces culpability. However, the conglomerate of disabilities that affect so many of those who appear before the court are not only matters of mitigation, they call for greater accommodation to be given within the processes of the court.

Procedural fairness requires the engagement of a defendant in the process which directly impacts on them. Engagement requires an understanding of what is happening and an ability to participate in the decision-making process.

The presence of disability, intellectual disability, mental health conditions, neuro-disability, acquired brain injury, in addition to the under developed brain, requires special consideration when it comes to court process.

I want to detail what the experience is in the Youth Court, describe what the characteristics are of those who appear and to make the point that those characteristics do not disappear when they turn 17.

They are static factors which a young defendant carries throughout their life.

Jurisdictional age limits are arbitrary and do not reflect actual development. Arguments about the Youth Court age limit will perpetuate this arbitrariness. In my view, it is more useful to argue about age appropriate processes in any court.

The processes in the Youth Court, and the multi-disciplinary teams that operate in the court, are designed to recognise the immaturity and the likely presence of disability, as well as a history of trauma. The young age means that the history of trauma is likely to be recent and the effects still raw. But this also means that the opportunity for redirection of their life trajectory is real.

The research shows that young people – into their mid-twenties – have demonstrably different brain architecture than adults2. Executive functioning, assessment of risk and consequences, is undeveloped. The rate of development may be slowed further through the extensive use of alcohol and other drugs. If we put aside the overlay of disabilities, this delayed brain development itself is justification for a court process which recognises that limited executive functioning.

The numbers also justify consideration of whether courts are responding appropriately to this age group. Those aged between 17-24 account for 14% of the general population, but 40% of criminal justice apprehensions. Dealing more effectively with this age group can have a substantial effect.

So, against this background the question I pose is why do we suddenly treat young people as if they are fully competent adults when they enter the District Court? It is my view that we need to recognise that there remains a separate cohort of defendants in the District Court who require, as a matter of procedural fairness, a different approach and for whom a different approach is necessary for the delivery of effective interventions. If the court is to deliver an effective intervention we need first to have the engagement of the young person in the process, and all involved need to know of the challenges facing the young person so that responses are properly tailored to recognise those challenges.

What is seen in the Youth Court

It is instructive to consider what is known about those who appear in the Youth Court.

A considerable proportion of offending by young people is dealt with by way of diversion. This recognises that much of youth offending is reflective of immaturity and underdeveloped cognitive abilities. Many of those diverted from court process will not go on to offend into adulthood.

What this leaves us with in the Youth Court is young people who have been subject to intensely complex and often compounded underlying issues which are really challenging to them and those around them.

They present in court with a range of neuro-disabilities, mental illness, intellectual disability, dislocation from school, the effects of acquired brain injury, the effects of the trauma of sexual abuse and being brought up in a climate of family violence, alcohol and other drug dependency. I am talking about young people who have been subjected to neglect, deprivation, and a poverty of care.

2018 statistics tell us that almost all (98%) of children aged 10-13 referred for a youth justice FGC had been the subject of a report of concern to Oranga Tamariki. For those aged 14-16, most (87%) of those had been the subject of the same report of concern to OT. These figures are trending upwards, particularly for females.

Often with an absence of positive role models, this leaves many of these young people vulnerable to negative influence of others and seeking out gang life as a substitute for family.

The Youth Court sees increasing prevalence of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD). We know that increasingly we are going to see those affected by methamphetamine in utero - the “meth babies”.

We see those whose empathy development has been interrupted by exposure to family violence. Those who do not have the ability to express remorse.

We see those who have a communication disorder and who require a communication assistant to understand the proceedings and enable participation.

The multi-disciplinary team in the Youth Court has evolved to cope with these complexities. Accountability, instilling a sense of responsibility, promoting safety of the community, are not compromised by recognition of the needs of a young person. Properly engaging with the young person, creating a process that happens with them as well as to them, these are likely to enhance outcomes. Fundamentally, it is about fairness.

Neuro-disability and Acquired Brain Injury (“ABI”)

Recently in discussions with reporters about this issue, I referred to the “cocktail of disabilities” that we see in the Youth Court. We know that disorders grouped as neuro-disabilities (FASD, intellectual disability, dyslexia, communication disorder) are significantly higher in those who come to court than in the general population. Research in the United Kingdom, examining disabilities of those young people in custody revealed some startling results.

The report is sobering reading but the following chart tells enough of the story:

“Nobody made the connection:

The prevalence of neuro-disability in young people who offend”

Report of the Children’s Commissioner, England, October 2012

| Neuro-developmental disorder | Young people in general population | Young people in custody |

| Learning disabilities | 2-4% | 23-32% |

| Dyslexia | 10% | 43-57% |

| Communication disorders | 5-7% | 60-90% |

| Attention deficit hyperactive disorder | 1.7-9% | 12% |

| Austistic spectrum disorder | 0.6-1.2% | 15% |

| Traumatic brain injury | 24-31.6% | 65.1-72.1 |

| Epilepsy | 0.45-1% | 0.7-0.8% |

| Fetal alcohol syndrome | 0.1-5% | 10.9-11.7% |

Nathan Hughes and others Nobody made the connection; the prevalence of neuro-disability in young people who offend (Office of the Children’s Commissioner for England, October 2012).

The information I have from New Zealand health practitioners is that it is likely that the New Zealand population will exhibit similar prevalence rates.

We know that there is a high prevalence of Acquired Brain Injury amongst those who appear in the District Court. Acquired brain injury is any damage to the brain that takes place after birth, that results in deterioration in cognitive, physical, emotional or independent functioning.3

An acquired brain injury can cause a person to experience a range of cognitive impairments and emotional and socially challenging behaviours, including poor memory and concentration, reduced ability to plan and problem solve, lack of consequential decision-making, difficulty absorbing additional information, heightened emotions and reduced capacity to regulate these. They are also much more susceptible to depression, irritability, impulsivity, disinhibition and aggression.

Much like other disabilities, there is a spectrum for the extent to which a person’s capacity will be affected, but often it will not necessarily interfere with a person’s intellect or their physical appearance. A person with an acquired brain injury could experience the emotional and cognitive changes discussed, without the brain injury being recognised. For this reason, it is often referred to as a ‘hidden’ disability.Much like other disabilities, there is a spectrum for the extent to which a person’s capacity will be affected, but often it will not necessarily interfere with a person’s intellect or their physical appearance. A person with an acquired brain injury could experience the emotional and cognitive changes discussed, without the brain injury being recognised. For this reason, it is often referred to as a ‘hidden’ disability.

Ordinarily, less than 13% of the adult population would suffer from an acquired brain injury. On this basis, one would think that it is not a prevalent issue. Yet for all the reasons that I have just mentioned, if an individual has an ABI, it will dramatically escalate the likelihood that they will encounter the justice system.

Ministry of Justice with other agencies recently carried out some research into this. Using data linked from the Ministry of Justice, Corrections, Health and ACC4, the rate of prior recorded traumatic brain injury was examined. It found that:

This means that almost 50% of all adult offenders in prison are affected by an acquired brain injury. Given that this data was reliant on records of a hospitalisation and/or an ACC claim, the analysis is expected to significantly under estimate the actual rate of traumatic brain injury.

Other research is consistent with this assumption. In a 2005 survey 64% of people in prison reported having a head injury, and in 2017 a study of females in prison recorded that 95% of females in prison had a history of traumatic brain injury.

So, not only do we know that having an acquired brain injury will dramatically increase a person’s chances of coming into conflict with the justice system, we also know that once connected they are more likely to remain trapped within it, continuing to reoffend. In part, this is because the criminal justice system demands compliance with rules, instructions and processes that people with an acquired brain injury have difficulty following.

Consider the individual who repeatedly breaches bail, not understanding the implications of what they are doing, who appears sullen and non-cooperative, because they feel, and, are dislocated from the process happening around them. Those who nod to say they will be back in court on the 7th of September at 10am, but struggle to tell the time accurately let alone coordinate their movements to do so without support.

All the effects of acquired brain injury will negatively impact on their journey through the justice system, and make it more likely that they will be a lifetime offender.

Family violence

For the general population, the most common cause of acquired brain injury is a fall or a trip or a slip. Some will acquire, or worsen an existing acquired brain injury through abuse of alcohol and other drugs. Yet the most common cause of acquired brain injury for people in prison is being subjected to an assault.

This could be an assault sustained in adulthood, or concussion from sport. But when we remind ourselves of the deeply concerning family violence statistics in this country, it is not a far jump to conclude that family violence will often lie at the root of this. We know that approximately 80% of child and youth offenders under the age of 17 grew up with family violence at home.

Whether they were a direct victim of this, receiving beatings and experiencing head trauma, or witnessing it indirectly, their brain development will have been affected. Constant fear is not a good predicator of positive outcomes for these young people. For mothers who are pregnant and subject to violence, the levels of cortisol in the bloodstream so too can impact the brain development of the unborn fetus while in utero. We have generations of negatively impacted people from the effects of family violence.

In the space of one year, there were 119,000 family violence investigations by NZ Police. There is a family violence call out to Police every 4.5 minutes. In 80% of the call outs a child is present in the home.5

When we consider the evidence that only about 20% of family violence is ever reported, these numbers become even more grave. Tens of thousands of children in New Zealand are growing up in a climate of violence. And the effects of being subject to violence within the home, or of witnessing or hearing such violence, are severe: physically, emotionally and developmentally. Anxiety, fear, depression, PTSD; these effects will play out in other aspects of their lives and affect them in the long term.

For many, a history of childhood sexual abuse will result in them self-medicating, turning to alcohol and other drugs to numb the pain, with the risk of further cognitive impairment.

Education

The factors that I have mentioned are not stand-alone. A young person who suffers from any of these cognitive challenges is going to really struggle to remain in school, particularly when their behaviour is such that the schools would prefer they were not there.

Without proper supports in place, most will become disengaged from education at an early stage. Their parents too may have been dislocated from education. Almost 50% of young people in New Zealand who offend are not enrolled, excluded, suspended or simply not attending school.

Our court process on the first appearance will give a 20-year-old, who dropped out of formal education at an early age, who may have disengaged from school because of dyslexia, a bail form to sign. The process expects them to understand the legal jargon, “reside”, not “associate”, not “offer violence”, “not consume illicit drugs”. And we use words like “remand”. What does it all mean to a young person with the overlay of disabilities I have described?

Discussion

So, those are the complexities seen in the Youth Court and those complexities sit on top of the under developed brain.

Cognitive skills and emotional intelligence that mark the transition from childhood to adulthood continue to develop at least into a person’s mid-20s. Traits such as impulsivity, high susceptibility to peer pressure, tendency to be overly motivated by reward seeking behaviour, do not conclude at 17 or 18. Further, protective factors such as marriage, educational milestones and meaningful employment are happening at a later stage in a young person’s life. This contributes to an extended transitional phase from immature delinquency to mature.6

As such, decisions and actions undertaken by 17-24 year olds may be mitigated by their lack of maturity and sanctioning them like fully mature adults could have life-long consequences that harm the young person and communities and negatively impact on public safety.

All those who come to court under the age of 25 will have the cognitive shortcomings that the current brain science tells us about. In most of those cases in the District Court we need to then consider those additional complexities - the neuro-disability; FASD; the acquired brain injury; the alcohol and other drugs; dislocation from school; exposure to family violence; the mental illness.

Where to?

In the Youth Court, we have a multi-disciplinary team. We have forensic screening available in almost all our Youth Courts and full assessments and reports can be ordered. Forensic nurses are observing a young person’s presentation and interactions and hearing what is happening to effect interventions. We have education officers, and Lay Advocates. Communication Assistants to assist understanding. We have become more alert to the possibility of neuro-disability and mental illness, and are starting to confront the communication / cognition issues that may accompany acquired brain injury and neuro-disabilities.

I am not suggesting that it will be realistic to employ all these techniques and resources in a District Court context for adolescents aged 17-25, at least in the short-term. What I am saying is that we need to adjust and make changes where we can. We need to listen to the evidence of how challenging our system can be for defendants, and particularly young defendants, and I suggest there are lessons to be learned from the Youth Court process.

Procedural Justice

This could be at a very basic level of procedural justice. Procedural Justice Theory7 is the idea that a system that is respectful and fair results in greater compliance with the law, to the benefit of everyone. People who feel they have been treated respectfully and fairly by authorities, even while being sanctioned by them, are more likely to comply with the law and regard it as legitimate. Adopting an approach that is more cautious and treats all people as though they could be vulnerable in the interaction is likely to benefit everyone. This approach has been called ‘universal vulnerability’ by researchers, and what it looks like is: plain language; open-ended questions; and asking people to put information into their own words. A service that uses plain language to assist people with cognitive impairment, also assists people with low levels of literacy or whose first language is not English.

It does not require a focus on diagnosis, it zeroes in on what is important in the interaction: whether the communication is effective, understood and, therefore, fair. Equally, we need to be attuned to the common presentations of people with an acquired brain injury or neuro-disability. It is the process we see in solution focused courts such as AODTCs and the Youth Court.

A court room experience which results in cognition-impaired defendants feeling detached from the court experience, alienated by the confusing language used by judges and being otherwise ignored does not work in anyone’s best interest. By contrast, in a recent study in Victoria, Australia, those who have experienced solution-focused courts reported being much more engaged in the process, and felt respected by the way the hearing was conducted and how they were interacted with.8

The Netherlands first discussed the idea of distinct systems of justice for this age group in the 1950s.9 So what I am talking about is far from revolutionary. Three European nations – Croatia, Germany and the Netherlands - all allow youth over age 18 to be sanctioned in the same manner as younger youth in the juvenile justice system, including the possibility of being housed in juvenile facilities.

In New York, the very recently introduced ‘Young Adult Courts’ apply different processes to what they refer to as ‘transition-age-youth’ charged with misdemeanours. These courts vary from borough to borough, but common components include the following:

The court provides both mandated and voluntary social services overseen by the Brooklyn Justice Initiatives program. All participants are given the opportunity to partake in voluntary programmes and ongoing plan support, and services include:

Croatia refers to ‘young adults’ as those up to age 21. While they do not have special courts for this age group, they have a distinct procedure and departments within regular municipal courts. In Germany, they have a binary approach for those 18-21, where they can be sent either into juvenile justice (67%) or dealt with under the adult jurisdiction (33%).10

One important limitation for the US example however, is that it is used only for youth who have committed what they refer to as ‘misdemeanours’. The maximum penalty for a misdemeanour is 1 year imprisonment, making it equivalent only to a category one, or some category two offences in New Zealand. As most of these would be dealt with by diversionary means, or not make it to court anyway, we must keep this in mind.

Nevertheless, New Zealand has traditionally led the way in developing a comprehensive, consistent and effective youth justice system. So too, could it lead the way in utilising processes and procedures currently in existence in the Youth Court, for this group of ‘transition age youth’ who have progressed to the District Court.

The Youth Court processes reflect the legislative requirement to enable participation by young people and that requirement follows the Beijing Rules, the Convention on the Rights of the Child 1989, and the UN Convention on the Rights of the Disabled.

The Council of Europe’s 2003 and 2008 recommendations included that courts should be guided in policies and practice by the consideration that:11

The age of legal majority does not necessarily coincide with the age of maturity, so that young adult offenders may require certain responses comparable to those for juveniles.

These international considerations support the momentum toward diversion, minimum intervention, education, restorative justice and other constructive measures.

There are 25,268 unique offenders between the ages of 17-24 in New Zealand.12 This is a significant percentage of the criminal justice population, and I suggest one of the most malleable groups for which change could be effected. If we can make a difference in the life-course trajectories of this group of people through utilising appropriate processes within existing legislative framework, there is a chance of fewer becoming recidivist offenders, and consequently fewer victims in our society.There are 25,268 unique offenders between the ages of 17-24 in New Zealand.12 This is a significant percentage of the criminal justice population, and I suggest one of the most malleable groups for which change could be effected. If we can make a difference in the life-course trajectories of this group of people through utilising appropriate processes within existing legislative framework, there is a chance of fewer becoming recidivist offenders, and consequently fewer victims in our society.

How might a different process be achieved?

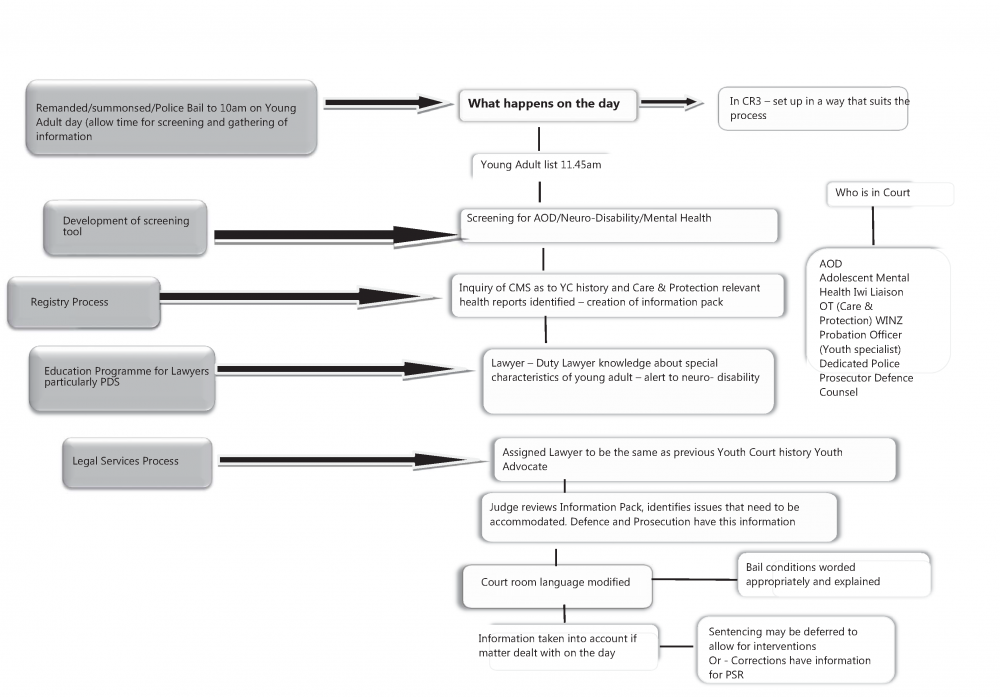

My proposal is for a process that separates out the young defendants and provides for hearing their cases in a separate block of time. It is for a process that harvests information about these defendants from existing court records and from screening tools used at court. It is for a process that in all respects takes account of the special characteristics of young people in general and enables identification of the particular disabilities of many. It is for a process that enables all in the courtroom to be alert to these special characteristics so that language and approach is modified accordingly.

The process that I describe in the following diagram is just how I see it without the undoubted benefit that will accrue from wider consultation, advice and discussion. It should be viewed as a preliminary sketch rather than the completed working drawing.

Why Porirua?

I am proposing trial in Porirua Court because:

Screening Tool Development

Knowing what obstacles to engagement are present is perhaps the biggest challenge in this process. The development of a screening tool, able to be applied in the short time available before first appearance, will be integral to at least raising a red flag or flags. The expert advice I have is that such a tool could be developed which could identify the possibility of neuro-disability. I am proposing to use a Postgraduate Psychology Intern from Victoria to investigate this (alongside other forensic process issues). The provision of an adolescent mental health worker (in place of the usual forensic nurse) will need to be explored. Access to mental health history would also be useful.

There will often be important information in Youth Court and Family Court files. (Care and Protection). Balancing the undoubted usefulness of this information against maintaining the integrity of confidentiality provisions in those courts will be an issue.

Evaluation

There will need to be an evaluation - does the process make any difference would be the question and how might the process be improved – lessons learnt and so on. If the process is effective then the long-term plan should be to apply it in all District Courts.

PROPOSED PROCESS

(Subject to consultation)

Development Process

1. Engage MoJ Policy and Operations

2. Engage with key agencies

3. Evaluation Plan

4. Post Graduate Psychology Intern (screening process)

5. Advisory Group:

Download PDF: (384 KB) [PDF, 384 KB]

1 This title, while descriptive, will require further thought and consultation – a working title only.

2 Elise White and Kimberly Dalve “Changing the Frame: Practitioner Knowledge, Perceptions, and Practice in New York City’s Young Adult Courts” (Center for Court Innovation, New York, 2017)

3 Centre for Innovative Justice, Jesuit Social Services, “Recognition Respect and Support: Enabling justice for people with an Acquired Brain Injury” 2018.

4 New Zealand Justice Sector Population Report 2018.

5 Ian Lambie “It’s never too early, never too late: A discussion paper on preventing youth offending in New Zealand” (2018) Office of the Chief Science Advisor at para 47.

6 Sibella Matthews, Vincent Schiraldi and Lael Chester “Developmentally Appropriate Responses to Emerging Adults in the Criminal Justice System” Justice Evaluation Journal (2018)

7 Thibaut and Walker, Procedural Justice: A Psychological Analysis (N.J Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1975) see also Tom R. Tyler ‘Procedural Justice and the Courts’, Court Review (2007) Volume 44, 26-32.

8 Centre for Innovative Justice, Jesuit Social Services, “Recognition Respect and Support: Enabling justice for people with an Acquired Brain Injury” (2018) at 34.

9 Youth Justice in Europe: Experience of Germany, the Netherlands, and Croatia in Providing Developmentally Appropriate Responses to Emerging Adults in the Criminal Justice System.

10 Sibella Matthews, Vincent Schiraldi and Lael Chester “Developmentally Appropriate Responses to Emerging Adults in the Criminal Justice System” Justice Evaluation Journal (2018)

11 Council of Europe Committee of Ministers Recommendation Rec (2003) 20.

12 Statistics sourced by the Office of the Principal Youth Court Judge from Ministry of Justice Statistics team. This figure represents the number of unique offenders in the year 2017.

This website explains many of the things you might want to know if you are coming to the Youth Court, or just wondering how the Youth Court works.

Visit website

Visit website

Ministry of Justice website with information on family issues including about going to court, forms and other times when you may need help.

Visit website

Visit website

For information about courts and tribunals, including going to court, finding a court & collection of fines and reparation.

Visit website

Visit website

On this site you will find information about our Supreme Court, Court of Appeal and High Court including recent decisions, daily lists and news.

Visit website

Visit website